In the late-1940s, Lou Hirshman, once a student at the precursor of the Samuel S. Fleisher Art Memorial in Philadelphia, became one of its teachers – and later its faculty director. We reprint a Fleisher blog post, in which the revered art school, administered by the city’s Museum of Art, rediscovers one of its own.

Rediscovering Fleisher’s Sophisticated Junk Collector

Posted By: Dominic Mercier

05/02/2017

Louis Hirshman hated driving.

His son, William, recalls being in the family Volkswagen with him one time, and his father kept a deathgrip on the vehicle’s interior handles for the entire ride. Hirshman’s preferred method of transportation was his own two feet, and he would make the five-mile walk from his home and studio in West Philadelphia to Fleisher nearly every day.

The walks were an “important time for him, almost meditation. I imagine a lot of ideas would go through his head and sometimes he would discover his found objects,” William says. “He walked in all kinds of weather and when his shoes would get holes in them he would just shove cardboard in there or would resole them with old tires.”

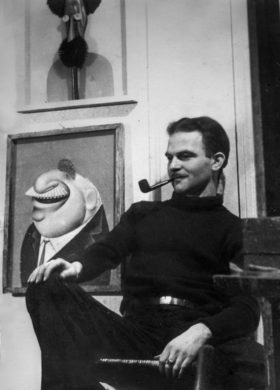

Above: Louis Hirshman with a number of his caricatures.

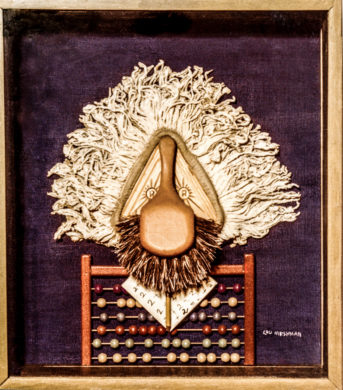

A “sophisticated junk collector,” those found objects were the basis for the caricatures of movie stars and politicians for which Hirshman is so well known. From his pre-war depiction of Hitler, who Hirshman skewered with a leather glove to represent the dictator’s famous sweep of hair and dustpan of manure for a body, to John D. Rockefeller and his rock shale body, no one in the public eye was safe from Hirshman’s withering wit. A Swiss Army Knife of an artist, Hirshman didn’t just rely on the objects he found, but he also created the food items that play pivotal roles in so many of his works, devised an ingenious way of attaching everything to the substrate, and framed the works himself.

After his immigration to Philadelphia from the Ukraine in 1909, Hirshman, was a fixture at Fleisher from his first days as a student of the Graphic Sketch Club in the 1920s until his retirement as faculty director in 1977. In the years between, he did a stint in the Army, studied in Paris and Italy on scholarship, and helped produce one of the first examples of avant-garde film making in the country with Story of a Nobody, which was housed in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art until its degradation and disposal in 1956.

Above: Louis Hirshman, left, with Fleisher faculty members Mac Fisher and Louise Clement-Hoff.

At Fleisher, he instructed both adults and young artists in a number of mediums, with one former student remembering that he used to call refer to himself as “Mr. Hersheybar” in the Saturday children’s classes. And despite his Jewish faith, he regularly organized Fleisher’s children’s Christmas parties. But despite his impact on Fleisher’s young students, his own children, William and Deborah, couldn’t help but feel a little left out of their father’s life.

Above: Louis Hirshman, left, oversees a Fleisher landscape class at Manheim Academy in the 1970s.

“He said one time,” Deborah recalls, “when we went on vacation that was his vacation. He only went with us once to the seashore.”

“But he had a fantastic laugh,” William adds. “If you could get that man to laugh it would fill you with pure joy.”

Home during the day while Deborah and William were at school and then gone until about 10:00 p.m., when he would return home from Fleisher’s evening classes for his regular late-night meal of soup, crackers, and Alfred Hitchcock Presents, their paths did not cross all that often. The majority of the time they spent together, Deborah says, was on the weekend after Fleisher’s Saturday classes ended. Much of his free time was spent sequestered in his studio, a sanctum were few were allowed to tread.

“We were his children,” William says with a chuckle. “But I always thought his real children were in his studio.”

Not one to promote himself and with no gallery representation or manager, Hirshman’s artistic legacy began to fade after his death in 1986 and the gap between him and his children widened.

“Before he died, he said to me and my mom, ‘take my pictures and put them in the closet,” Deborah recalls.

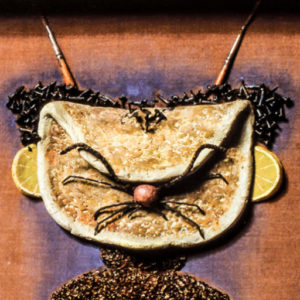

Above: Hirshman’s caricature of Albert Einstein.

His most recognizable work, a caricature of Albert Einstein with a mop for a head, a brush for a nose and face, and an abacus for a body, moved from its spot in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s registrar’s office to storage and a number of other works have been lost or were possibly stolen.

In an effort to get to know their father even better, track down nearly 40 missing works, and allow those who knew him to further explore the shift in his work that occurred after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Hirshman’s children created hirshman-art.com. William Hirshman says he is particularly eager to locate his father’s caricature of Fidel Castro, with a beard of chain, a donut mouth, and a hot dog cigar.

“I always recognized him as someone who could do something special. But it’s only as the years have gone on that I’ve appreciated what he did more and more. He was, in my mind, a genius and I don’t think I’m overstating it,” William says. “In a way, now, I talk to my father more than I did then.”

Above: Louis Hirshman with Louis Hirshman.

William hopes Fleisher’s vast community can help him even more. He is actively gathering stories from former students and faculty members to learn as much as he can about his father, and anyone with leads on missing artworks can submit tips through the website. For more information, visit hirshman-art.com.

(Editor’s Note: To see the original post, go the Fleisher website.)